S.J. Shank

The Knave of Graves

"With The Knave of Graves, Shank delivers an entire cosmology in shovelfuls of earth. Cerebral dark fantasy from a terrific storyteller."

– Coy Hall, author of The Owl Men of Shanidar"A mystic, slow burn story of dark ancient power, chilling yet humourous bargains, faith and religion, cozy yet comedic, at times quirky and absurdist, and reminiscent at times of Midnight Mass."

– Ai Jiang, author of Linghun"An elegantly written historical dark-fantasy filled with heart, humour, and dark magic."

– Suzan Palumbo, author of Countess

Now Available

Books

Mailing List

Subscribe to the mailing list and receive a free copy of Rare Specimen and Other Stories.

The dead sleep safely in Jeppo's graveyard. For the most part.

Jeppo loathes his hometown and he can scarcely tolerate the townsfolk. Mostly, he despises his life as a gravedigger. He went to the Academy in the south, after all. He was never meant to take up his father’s shovel.When a wicked sorcerer arrives at his gate demanding the bones of the local saint, Jeppo has no objection in principle. But he fears the wrath of the night hag, to whom he has been selling corpses for years.Jeppo must choose the lesser of two evils, and do so quickly. The spiraling feud threatens to spill innocent blood … and worse still, his darkest secrets.

Carthago Nova Press, 2025

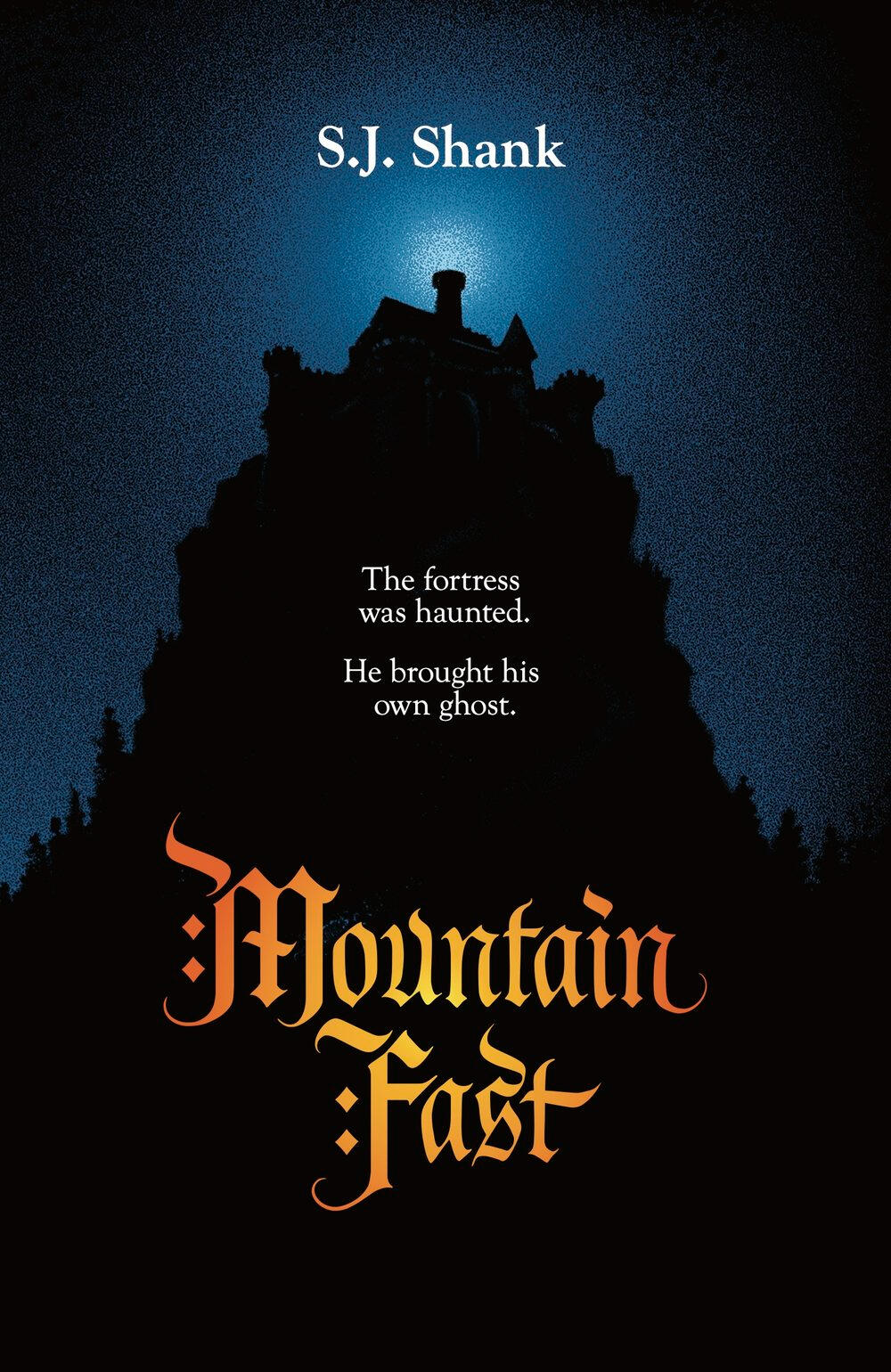

The fortress was haunted.

He brought his own ghost.

Hungary, 1468.At Kuszkol, the old-timers say, shadows walk and men go mad. But sixty years after the remote mountain fortress was first abandoned, it is attracting soldiers once again.The bishop’s messenger András carries a letter for the new commander. On his party’s northward journey, he downplays the old tales. Yet he cannot explain why the castle’s beacon should burn the night before their arrival. Nor why, once they arrive, the garrison is missing. Nor can he explain the mysterious charcoal figures they find etched on the walls.By the time they settle down for their first night at Kuszkol, András faces an even more pressing question—why is he speaking in his dead wife’s voice?

Carthago Nova Press, 2024

Eight tales of weal and woe.

An oracle whose gift for prophecy is infectious …A watchwoman who guards the mouth of a wormhole …A monster hunter who worships her quarry …A mage whose sorceries are trapped by stitched lips …Welcome to the dread futures and grim antiquities of S.J. Shank. Together, these eight stories weave a feverish tapestry of misplaced loyalties, tainted victories, and survival by the leanest of margins.

Carthago Nova Press, 2023

Review Links

If you enjoyed one of my books, please consider leaving a review using the following links.Reviews make the book world go round, and every one makes a big difference. Thank you!

The Knave of Graves

Chapter 1

Jeppo Kärkiskjo had not once wept for those beneath his feet, but he had become a great observer of grief. At today’s funeral, he observed how Mrs. Puntasakjo bawled on her father’s shoulder. How tears dripped from the widow’s cheeks. He listened to wet-lipped wails, gasping sobs, and that tedious question repeated over and over again. “Why?”He had seen and heard it all before, and he judged it an adequate performance. That was, until, the priest-doctor waved him forward to lower the body of Vuuli Puntasakjo into the grave. At that moment, with all eyes cast downwards, the widow lifted the hem of her skirt. To preserve her embroidery from the grave soil, he thought at first. Yet, her act revealed stockingless ankles to all.Hunched over the dead man, Jeppo pretended to smooth the shroud that he might glut himself on the sight. The lady’s spotless flesh. Her ankles’ delicate proportion, no thicker than his wrists. When he stepped from the grave and back into the crowd, he began to watch her more closely.

“What will I do? What will I do?” Mrs. Puntasakjo groaned. Jeppo noticed she did not address her handkerchief or even her cold husband, swaddled at the bottom of the shallow pit, but the other mourners. She even swiveled her eyes, as lovely and round as waxed moons.“To whom shall I turn now?”The mourners stirred. Ears perked. Noses lifted, sniffing opportunity. Mrs. Puntasakjo’s question was honest and also proper, for none could deny her new vulnerability. But, Jeppo thought, her asking was not specifically appropriate to this time and place. She had all but announced her wish to throw off the widow’s shawl.Jeppo waited for the ceremony to end by his vine-clad cottage, a modest little home near the wall that commanded no attention so near the magnificence of St. Vattis’s tomb. He chewed the stump of his unlit pipe and he thought of Pajva Puntasakjo’s question, and the solace he might give. Then he asked himself a question of his own: Why should it not be me?Why should the widow not turn to Jeppo Kärkiskjo for comfort? Who knew better how to keep another safe?When the priest-doctor finished his prayers, Mrs. Puntasakjo pressed her fingers against the arm of one man after another, thanking each very sincerely for paying his respects, warming each with her smile and the flutter of her dewy lashes. And, with a question asked of himself and left unanswered, Jeppo asked himself another: Why should she not thank me?He acted impulsively then. As the mourners began to take their leave, rather than remain standing at the graveside, leaning upon his shovel as solemnly as a cavalryman upon his saber, he followed. The widow cast a final glance at her husband’s grave, and her eye alighted for an instant upon him.She was nearing the cemetery gate and Jeppo quickened his pace. He passed the widow’s stooped aunt who quashed clods of earth with her cane as though they were spiders. He passed the widow’s slouching cousin, who would have been as tall as the lintel if ever he stood up straight and who, though his cheeks were dry, appeared in that procession saddest of all. Jeppo passed the first fellow who had received Pajva Puntasakjo’s thanks, then another, and was near to her elbow when the priest-doctor’s hand reached out to seize his own. Rev. Miklaja leaned towards Jeppo, his eyebrows drawn together like two squirrels colliding. “Have you not received your fee, gravedigger?” the priest-doctor asked.Jeppo pulled his arm away and knew his face was darkening. “I have.”“Have you had problems, then, with—” and here the priest-doctor lowered his voice and patted his long curing-knife, “bogeys? Need you the strength of my prayers?”“I need not your prayers,” Jeppo said. By his tone, one might have imagined the priest-doctor offered to knot Jeppo’s neckcloth.“Hmm.” The priest-doctor momentarily glanced at St. Vattis’s tomb before he stepped backwards. He retreated towards the gate still facing Jeppo, as though to make sure the gravedigger stayed in place. “Then good day to you, sir.”The priest-doctor’s nod was so slight that Jeppo did not bother to return it. Besides, he was looking over the priest-doctor’s shoulder to see he had missed his chance. The widow Puntasakjo had already left his domain, braced on both sides by lithe and manicured men who none would call unhandsome. Neither man was her father.Jeppo waited until he could no longer hear the mourners chattering before he began to fill the grave. He picked up his shovel and threw dirt over the dead man’s face.He had known Vuuli Puntasakjo his whole life. Known him too well. When Jeppo was seven and Vuuli a young lout of fourteen, Vuuli had convinced him to splash water on a beehive. The resulting stings had earned Jeppo the nickname bee-kisser for the ring of welts that had circled his lips.When Jeppo was twelve, Vuuli had pulled down his trousers in Luukarokja Square during the Pantomime of Blossoms, just as the players were circling to make their collection. That had earned Jeppo the nickname worm-coin, for what he dangled above the plate.Then when Jeppo was twenty-nine—eight years before this day—when he was newly returned to Vattivoja to take up his father’s trade, Vuuli was not spare in his mockery. It was Vuuli who first named his condition when even Jeppo’s teachers had merely patted his back before the Academy’s doors closed behind him. It had been Vuuli who had stumbled drunkenly across the floor of the sourmilk shop to hang a brawny arm around Jeppo’s neck and loudly proclaim his old friend the could-have-been had returned broken-winged.Jeppo never spoke to Vuuli again after that day. Tried never to think of him. Not until six weeks earlier, when Jeppo heard a rumor that Vuuli had left the brickworks vomiting and that the spell lingered longer than regular milk fever. That was when Jeppo began to hope. He sought out news of his old adversary and was gladdened by every detail of Vuuli’s decline. He spent his mornings daydreaming over his porridge, imagining less his enemy’s suffering than the moment of his dissolution and final erasure, the moment Jeppo might stand alone over Vuuli’s open grave, shovel in hand.“Now you are in my keeping,” he said to the corpse at his feet. “Hark my laughter—ha-ha!—you limp and leaking sack of mud. For I shall fête your wife in private. I shall lay these hands on her hips!”Jeppo dropped the shovel. He walked the circuit of the high stone walls whose four sides were his frontiers. He ran his fingers over the phylactograms that were inscribed at waist level, those grooved glyphs he repainted with red ocher every equinox, and felt the potency humming through the stacked formulae so that the whole web was as taut as a zither string. The reverend was a fool to think any bogey could ever trouble him behind this line.The graveyard’s walls concealed his tiny khanate from all, save from two vantages. First, the iron bars of the cemetery gate looked westward onto the path that wound through the Tuuliwood, past the gristmill and then round another bend towards Vattivoja. Second, to the south the land rose and the trees thinned where Master Eksa kept a pasture. Sometimes Eksa’s po-faced girl walked the hilltop to gather cow patties for the hearth or to strike the heads from daisies with her rowan switch.He checked these sight lines. No one observed him.He entered his shed, fetched two wooden planks, and dragged them to the grave. Vuuli lay three feet down in his hole, but rather than fill the space with earth, Jeppo laid the planks atop the grave’s length. He then fetched an old canvas and placed it over the boards so that no dirt could fall through the cracks. Upon the canvas he laid two sheaves of hay that rose a foot higher. He covered these sheaves with yet another canvas that was so filthy that, from a distance, it resembled soil.At last he took up his shovel and covered the cloth with as little dirt as was necessary to create a false mound over the grave. The earth that should have filled Vuuli’s grave remained piled upon a sledge where Jeppo had shoveled it the day before. He pulled the sledge behind the caragana bushes that grew beside his cottage shed.The heavy sledge offered no challenge for him, for the rope he used to pull it was enchanted. It was his most precious possession. His first gift from Kuumasta, and the last freely given. With this rope, no matter the burden, no matter how stony or muddy the ground beneath the runners, he could pull loads of excess grave soil as easily as a horse pulling children across a frozen lake.Thus, when he returned to Vuuli’s graveside, his brow did not shine, nor did the muscles in his back or arms complain. He sucked on his pipe, the bowl glowing with every pull, and imagined the table Mrs. Puntasakjo might keep. He imagined how, at the end of day, she might slip off her sabots to wash those stockingless feet.A cloth pulled over a high arch. A reddened heel. A basin and splayed toes beneath clear water.He puffed on the pipe and studied the grave before him.“Here lies Vuuli Puntasakjo. For now. See you soon, old friend.”

Mountain Fast

Chapter 1

Pál’s knuckles rested on the table. Dry blood filled their creases and flecked his swollen lip. A fissure in the wood held his attention. Like a convict marching to the stocks, he would not look at me. Nor would my brother-in-law answer. I tried again. “Did you know this lad? Was it one or many?”He stared down with such force his pupils bobbed beneath the lashes. He did not move his eyes from that dark little cleft.“Perhaps you were simply misunderstood,” I said. “It has happened to me. You must be mindful of others and how they take your meaning.”He slid a crumb beneath his thumb.“At your age, boys turn savage,” I said. “Some men never outgrow this.”Pál flicked his head. I could not tell if he meant to shake it or to dislodge a hair from his brow. I waited for him to say more, to tell me I was wrong. To tell me that there was good reason for this latest scrap. That it was not senseless and that he was no ruffian. For a time we sat in silence, just the two of us, alone as we had been these last months. No stew bubbled on the fire. Half a week’s dirty crockery crowded the table about our elbows.Soon I would have to go. I tried one last time. “Did you know this boy? Tell me his name and I will make this right.”Pál’s voice broke, “I did not know him.”I leaned toward him and reached for his wrist. He shifted his arm before I could take it.“A stranger did this to you? Why would he do that?”He flashed his eyes at me. Despite Pál’s new height and the size of his hands, I thought that if I continued to prod, tears might flow. I could not decide if this was for the best. He had come to me an orphan but he was well down the road to manhood. How far, I could not tell, nor why he so easily strayed.“You owe him nothing,” I said. “You must not protect him. Tell me his name and I will speak to his father.”“His father?”“Yes,” I said. “I will not stand for this brute treating you so.”“You have no grounds to speak. Not on my behalf.”He pulled his arms across his chest and found a tower of clutter on which to rest his gaze. There was no chance of loosening that tongue now.I pushed back from the table and stood. I studied Pál for a long moment. He did not look up. He had Annaka’s stubbornness and of late he had developed his sister’s talent for pique. It did not matter if I told him to stay indoors today to tend the fire. He would not listen and I could not blame him if he left. This cottage had become unbearable since we lost her.“Terézia will be by later with our supper,” I said.“My great luck.”“You are in no position to complain.”“Even a beggar would protest eating her tripe.” He turned those fierce eyes towards me. This time he did not look away.“Only those new to their vocation,” I said.“I will not count slop among my blessings.”“Terézia has only treated you well. You must never repeat such nonsense outside these walls.”“Else what?”I let his childish defiance hang, awaiting a flush of shame. But there was only anger coloring those cheeks. His thrust-out chin did not lower an inch.“It frightens me,” I said, “your ignorance of how far a man might fall.”His smile broadened. I left him grinning like a fiend.I saddled Fejes and began the short ride into town. Soon I passed through the gates and was climbing the plaster and timber corridors of Veszprém’s narrow streets. My destination was the palace upon Castle Hill, where my master, Bishop Albert Vetési, would hand me a letter to deliver. I would depart at dawn, and if His Excellency’s correspondent lived in Sopron, I would return in five days. If he had written to Székesfehérvár, as little as one. If Debrecen though, eleven or twelve nights might pass before I was back home again.The townsfolk squeezed past my horse and jostled my knees. I paid them no mind. Instead I studied the sky, searching for the cause of this unseasonable warmth. The mellow autumn light easily rolled back the chill of long nights, and the quiet breeze whispered no word of rain or snow. Ideal weather for travel. Good fortune for the days ahead, but at that moment I felt no gratitude.A child darted in front of me, bringing Fejes up short. The boy carried a roll of leather in the crook of his arm. He gave no backward glance at me, and I watched as he rushed beneath the awning of a cobbler who stitched hide cutouts into useful forms. The cobbler marked me and bowed his face, and at his word the boy turned and shouted an apology.A little apprentice. Five years younger than Pál, and already more advanced in his career.I had never had such thoughts before my wife died. No one had fixed my future, so I suppose I had expected Pál would find his own way. Now I knew I had erred. I was losing faith that he might find success through chance. He was not fit for a life of accident. Annaka was no longer there to care for him when I was on the road. In her absence, he had taken to tramping through town, seeking out his new friends who passed their shiftless days talking of bold futures, only to pester townsfolk for coin enough for wine.At the gate to Castle Hill a grizzled old-timer leaned against the wall next to a cold brazier. He appeared to be sleeping on his feet, but the sound of Fejes’s clopping hooves opened his eyes a crack. This veteran was named Jakab, the least valuable member of the king’s Black Army. He had arrived the past summer, and I gathered he was sent to Veszprém as a sort of exile. It was said he was as vicious as a weasel in close-quarters, but since arriving he had only distinguished himself by running dice games that ended in hard words. That, and his penchant for drink. He was suffering its after-sickness now, I guessed, and had no doubt been assigned this standing post in punishment.Recognition took and sleep lifted from his eyes though he made no move to right himself. His watchful look lacked any deference or hint of amity. I commanded none of the former, for it was not my rank but only my role as messenger that set me ahorse. As for the latter, I knew him only by his reputation, and perhaps he divined from my own expression what I thought of him. And perhaps he only knew me by my reputation, or more correctly my wife’s, for the story of her life and death was well known throughout the town. In the months since, strangers sometimes crossed themselves when they thought my back was turned.“Has the bishop’s visitor from Croatia departed?” I asked.The veteran stared at me. A vague hostility, like that of a dog whose boundary marking had been crossed, kindled in his eye.“Has he?” I repeated.“How the hell should I know?”I had half a mind to dismount and box the man’s ears. That would be a mistake, not least because I owed my calluses to handling tack, where his were earned drilling that he might better kill.Fejes, knowing what was best for me, stepped forward. As I passed, Jakab pressed a thumb to one nostril and fired the other like a cannon. He closed his eyes again.My horse led me to the stable. I left her there with the stable boys before crossing the yard’s pavement on foot. From the glowing ovens wafted the smell of the evening’s bread. In the palace, the vestibule blazed with candles illuminating a sainted heaven upon its ceiling.The bishop’s apartment was closed, so I set down my messenger satchel to wait, wondering if the maid Sára might wander by to wish me a good day. By some twist, this maid had come up in my last conversation with Terézia, and my sister was so full of details about the young widow I wondered if she had come prepared.My sister had said that, like me, Sára was alone. She was still young, had kept her figure, as I had no doubt remarked, and her two little girls were the sweetest creatures. And strong. Both had stayed dry-eyed the day their papa went to the churchyard as they held up their mother’s arms. Sára came from farmers attached to one of the bishop’s manors, simple folk who had not hesitated to take her in when her husband was lost. Word was her grieving was near its end and she was looking to move on.Perhaps this maid and my sister colluded. All I knew was that Sára always smiled when I spoke to her, showing the tips of her teeth, and that she looked at the floor when she curtsied in a way I found most charming. But Sára did not come along to dust the corridor’s statuary this day, and I waited alone, idly twisting my wife’s silver betrothal ring about my finger. I exchanged one-word greetings with the clerical secretaries who brushed past, and adjusted my footing as my knees began to ache. I had done nothing wrong, but like Jakab, I was left standing.The memory of the miserable old dog chased away all thoughts of Sára’s slender wrists. Suddenly, and with a sinking heart, I saw how Pál might turn out.The bishop’s door opened. Out stepped a big man who boomed his farewell, the Adriatic still sparkling in his eyes. The Croatian ambassador glanced me over, noticed my messenger’s bag, then returned his gaze to study my face. I had become accustomed to this sort of lingering appraisal. He, like so many far and wide, had heard the story of the messenger’s doomed wife.Pál, I realized, must encounter this same look every day.“András. Enter.”The sun threw fishnet shadows through the leaded glass. The bishop sat alone at his table, poised over rows of letters and charters that covered the surface like overlapping scales. Upon these records he had laid a bounded volume, his lectern forgotten in the corner. I recognized the book as a work of Greek statecraft. He had had me fetch it from the Universitas Istropolitana in Pozsony that summer. Despite the warmth of the light splashing across his broad shoulders, His Excellency wore a fine velvet cape, as red as ripe cherry, for later that day he would preside at the wedding of one of the Essegváry heirs.He waved me forward without looking up from the tome. His finger slid down the parchment and turned the leaf. He contemplated the new page for a moment before he placed a string, closed the volume and set it aside.“You travel to Buda.”“Yes, Your Excellency.” Four days.“I would that you hand my missive to the chancellor directly.”“Understood, my lord.”The bishop withdrew two sheets from a leather portfolio and reviewed them. I waited with my hands behind my back as he scratched out a postscript. Needless to say, Albert Vetési was one of the greatest men in the realm. He was once the land’s chief justice. He led the king’s delegation to Naples. My place as one of his messengers was secure, but Annaka always wanted me to make better use of my position. I had always resisted, until I surprised myself this day by speaking out of turn.“I have a brother-in-law, my lord. A boy yet, really more of a son.”Vetési’s eyelids fluttered as he registered that I had broken my silence. After writing another line, he set aside his quill and looked up from his desk. “Yes,” he said. “You spoke of him once before.”Despite my twelve years of service, I squirmed beneath his gaze. The gold upon his fingers, the precious stones at his neck, did not hint at his authority. Albert Vetési had met the Pope in Rome. He owned this city. The county was his.I was mortified to have broached the matter with my master. It was not my nature to preconceive the path ahead, I just followed it. It had been she who had pestered me to raise Pál’s career with the bishop. She had harried me since he was eleven. It had been the great quarrel of our life together. With Annaka’s death, I had surely prevailed, yet here I was suddenly capitulating.It was the latest instance of a strange new habit of mine, as if some rebellious part of me thought to make up for Annaka’s absence by acquiring her concerns. I often found myself thinking of tasks outside my domain, matters I had never paused to consider—the washing, grinding corn, batting cobwebs down from between the rafters—chores I now paid a neighbor to perform and towards which I felt a new and vague disdain. I found myself thinking, too, of grander matters—the movements of the Black Army from front to front, whether the revolts in Erdély would spread west, the rumored estrangement between the Archbishop of Esztergom and the king. The affairs of the great, upon which few as powerless as she wasted a thought. Even I did not, though as His Excellency’s vehicle, I often passed through the thick of it. I had never cared.The bishop watched me closely. He showed great patience, even interest, I would say. I had been told that he spoke to Annaka privately in her cell the day she died. Perhaps she had asked him to look after Pál.No. The bishop had not even intervened to save her. Yet they had spoken, about what I did not know. It was a question I had tried to leave unanswered for it sickened me to dwell upon it.“He is near enough a man,” I found myself saying. “I have no proper trade to pass on to him. It is time he found his place.”The bishop returned his attention to his papers. Instead of resuming his letter, he moved the leaf aside and replaced it with a fresh page. As he wrote, he said, “They need men at Kuszkol. A fortress in Trencsén County. It is comparatively safe. Send the boy to the garrison with my recommendation. The marshal will look after him.”Without a further word I had secured Pál his future. Two hundred miles from home.